I was fortunate to sit and talk with him about his practice, and also participate in an exchange of knowledge. The following were things that he conveyed during conversations in 2002 and 2003 about the traditional Samoan Malofie.

I was fortunate to sit and talk with him about his practice, and also participate in an exchange of knowledge. The following were things that he conveyed during conversations in 2002 and 2003 about the traditional Samoan Malofie. Tattooing tools are truly sacred and are passed on to an apprentice by the tufuga when the tufuga deems it appropriate. The apprentice must serve the tufuga at every moment and absorb everything that is spoken by the tufuga before he is deemed worthy to receive his own tools. This includes understanding the stories that accompany the tattooing, the specific construction of the tattoo, and how to each session is devised according to longstanding traditions. This also includes understanding the techniques of using the Au and Sausau (the traditional tattoo comb tool and tapping stick - called Hau and Hahau/Sausau in Tongan) and the science of stretching the skin when tattooing - toho kili or fusi kili.

Tattooing tools are truly sacred and are passed on to an apprentice by the tufuga when the tufuga deems it appropriate. The apprentice must serve the tufuga at every moment and absorb everything that is spoken by the tufuga before he is deemed worthy to receive his own tools. This includes understanding the stories that accompany the tattooing, the specific construction of the tattoo, and how to each session is devised according to longstanding traditions. This also includes understanding the techniques of using the Au and Sausau (the traditional tattoo comb tool and tapping stick - called Hau and Hahau/Sausau in Tongan) and the science of stretching the skin when tattooing - toho kili or fusi kili.Once given the tools, the apprentice is bestowed the Suluape title, and is required to perform a certain number of tattoos and remain in the service of the tufuga as an au koso (stretcher). He is also to understand how to conduct preparations for the ceremonial blessing or sama. Once the apprentice has completed a set number of tattoos and is able to construct and care for his own tools, he will then be bestowed the title of Su'a. Once a Su'a, he is then able to carry on tattooing and will begin carrying out the sacred sama ritual with each individuals he completes. This is overseen by the tufuga for a time until the apprentice is found able to fully carry out the tufuga tatau traditions solely.

With the advent of Westernized individualism and a culture of instant gratification, there have been some Samoan and other Pacific Island individuals who have attempted to bypass the above tradition and construct their own tools and tattoo without a cultural license to practice. Many of these tattooists are untrained, untitled, and unaware of the damage they may be causing to individuals who are attempting to reconnect with their culture.

There are individuals out there walking around with traditional tattoos that are crooked, poorly constructed, and strange looking with incorrect design placement. Furthermore, many of these tattooed individuals did not undergo proper preparations before the tattoo, nor did a receive a proper blessing after.

If you come across a traditional tattoo artist, it is important to find out who their teacher was, how long they apprenticed for and where did they get the tools from. This might offend the tattooist so sometimes relying on gut instincts is probably the best defense against these self-proclaimed tufuga.

Each person tattooed by a student of the Su'a Suluape clan also recieves the traditional family signature which occurs as the final marks on the body. These markings are very distinct to the this clan and anyone tattooed by the Su'a Suluape clan will recognize this mark when seen on another person. This is another way to ensure the tattooist autheticity.

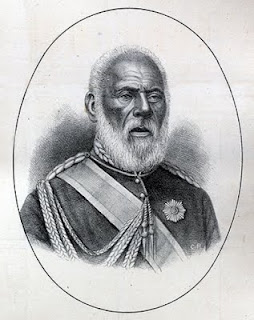

From my last conversation wtih Su'a Suluape Petelo, he had only bestowed the Suluape title on 5 individuals, and the Su'a Suluape title on 3 individuals. This is important considering the amount of "traditional" tattoo artists that are growing in numbers in America, New Zealand, Samoa, and Australia.

What's the Big Deal?

Many have asked this as well. I hear comments like "we don't live in Samoa so why do we need to go through all that tradition crap?" In order to preserve the true integrity of wearing a traditional tattoo, you must respect the traditions that have held it together for hundreds of years. Naturally, the malofie has evolved from pre-western days as a result of each tattoo family; however, many modern day tattooists (both Islanders and non-Islanders) have taken it upon themselves to 'revolutionize' this sacred practice, turning it into a fad and popularity contest for the artist's own selfish recognition. This was never the intent of wearing a traditional tattoo. As Suluape tattooed individuals, he would remind them of their duty to take care of their family, being responsible to cultural tradtions, and knowing that you represent more than just yourself by wearing the malofie.